My granddaughter Eleanor is 5 years old. She loves to have her photo taken. And every photo is just like her: beautiful.

Children need to feel beautiful. They also need to feel smart and good and loved. But it helps to have at least one person who makes them feel like a beauty.

When I was Elle’s age, that person was my granddad. He’d smile at me and quote Song of Solomon 6:10: “Who is she that looketh forth as the morning, fair as the moon, clear as the sun, and terrible as an army with banners?”

I wasn’t sure about the “terrible” part, but overall, I took it as a compliment. He especially liked my waist-length hair. Then my mother had it chopped off into a Pixie and Granddad bawled like a calf.

But the worst blow to my self-esteem came in second grade, when I hit my mouth on a tile floor and broke out my brand new permanent front tooth.

We couldn’t afford a porcelain crown, so the dentist covered it with a metal cap. Boys at school called it the Silver Bullet.

For years, I hated posing for school photos. The photographer would try to get me to smile, but I kept my lips clamped tight to hide the Bullet. In every photo, I looked like my grandmother when she was dipping snuff.

Finally, when I started high school, my dad worked some extra shifts at the mill to pay for a porcelain tooth. I was glad to get rid of the Silver Bullet. But I’ve never gotten rid of my dread of having my picture taken. It doesn’t stop me from smiling. I smile plenty. I just don’t like smiling for a camera. I avoid it whenever I can.

All of that is to tell you this. The photo that appears with a column is called a mug. In my 30 years of writing a column, I’ve had a series of mugs. They all look like different women:

_ The woman who wrote about juggling the roles in her life as the wife of a coach, the mother of three young children, and a reporter covering everything from parades to earthquakes to violence in schools.

_ The woman who described her husband’s battle with cancer, her children growing up, her father taking his life, and her blind brother’s struggle to live alone after losing his wife.

_ The woman who wrote about being a widow, falling in love, getting remarried, living in Las Vegas, speaking at fundraisers to strangers who treated her like family, and having eight grandbabies in nine years.

They were all the same woman in different stages of life. And they all hated having their pictures made. In the past 10 years, I’ve kept the same column mug, despite being nagged by editors (and they know who they are) to update it with a new one.

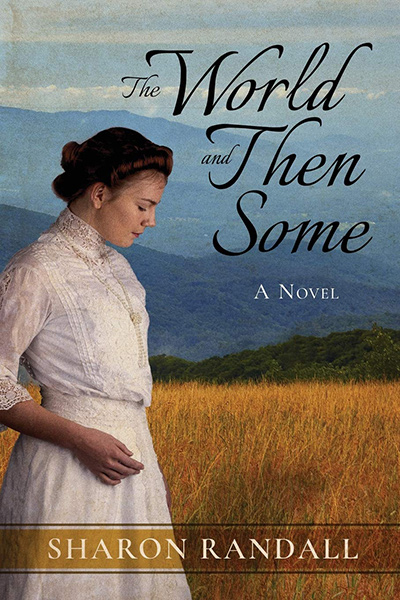

Recently, however, I finally published a novel that I’d been working on for years, and I forced myself to get a new photo for the book’s jacket.

The differences in the old mug and the new one are simple: In the old one, I have long hair, a big smile and look more like my daughter. In the new one I have short hair, less of a smile, and look more like my mother.

I sent the new mug to all the papers that carry my column to use as a replacement for the old one. And now I’m hearing from readers who say either:

_ They love the new mug.

_ They like the old mug better.

_ Or they don’t believe the new mug is the same person as in the old one and they want to know what exactly I did with her?

Once, long ago, I was driving my 4-year-old and his buddy Eric to preschool. We passed a parked car that was covered with a tarp and Eric said, “Look at that, Josh. Grownups are so dumb. Everybody knows there’s a car under there!”

As for the column? It doesn’t really matter if the mug is old or new. Everybody who reads it knows the age of the woman who writes it. And she is never changing her mug again.

Recent Comments